Women’s History Month: The Hewins Sisters

News Story

For Women's History Month, we're shining a light on some of the women from our archives who deserve to be celebrated. Will Roberts, from our Campaigns team, highlights the Hewins sisters – the self-published authors of ‘Lest We Forget: Being Some Account of the Smaller Incidents in the Great War’.

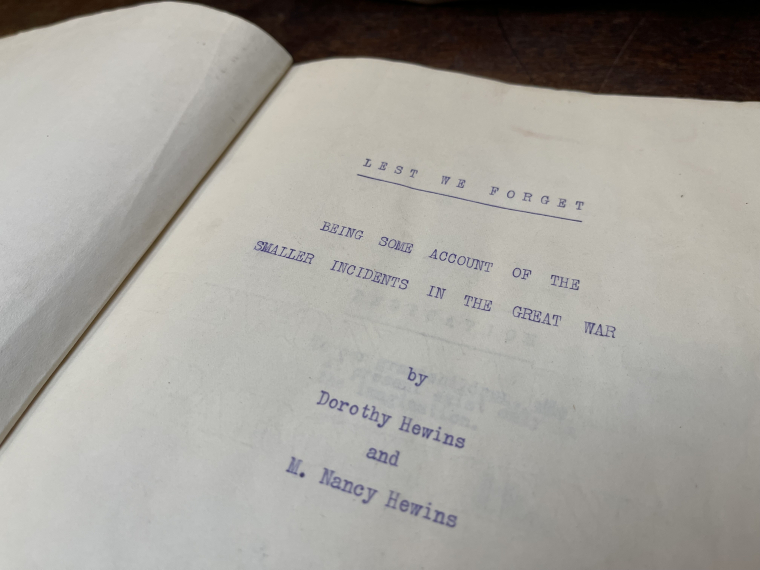

As a relative newcomer to the Bishopsgate Institute team, I’m still getting acquainted with the many lives and stories that live in our archive. As such, when we made the decision to put special focus on some of the women found therein, I sought the help of our Interpretation Manager - and all-round fount of knowledge - Dr Michelle Johansen. On the topic of notable women, an extensive list was provided, and narrowing it down had the potential to be tricky. Fortunately for me, I almost instantly gravitated to the Hewins Sisters and their memoir, Lest We Forget (see above for its subtitle).

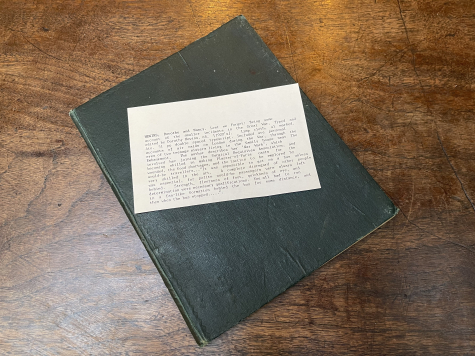

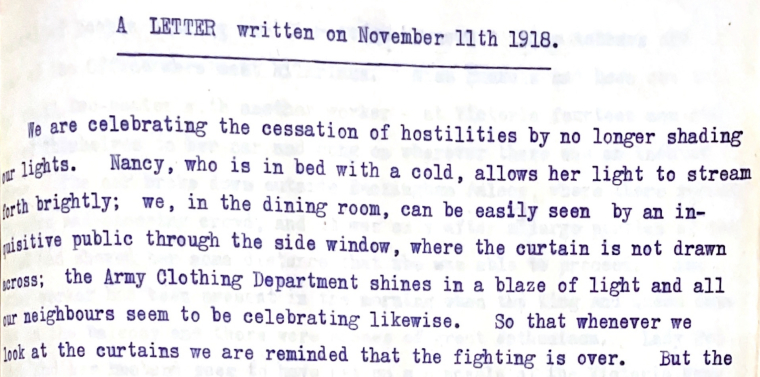

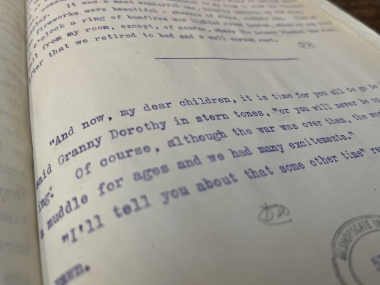

Within our archive there is only one item relating to the Hewins Sisters: the aforementioned memoir. A slender, muddy-green volume that could easily be mistaken for an old notepad, its contents run to just fifty pages, typed and edited by Dorothy Hewins - as the note inside so handily informs. It's something that could have been lost to time, forgotten on a shelf, but fortunately for me – and hopefully you – Michelle Johansen discovered it. Michelle has been using this item in her hands-on history courses and workshops since 2011.

As the title suggests, contained within these pages are Dorothy and Nancy Hewins’ account of life in London during the First World War. Though it’s not stated in the text, further research has revealed that at the time of writing, Dorothy was aged 24, and Nancy was 15. The bulk of the book seems to have been written by Dorothy, though Nancy makes her presence felt on several occasions – especially in instances where she relishes undermining her older sister.

I have not seen her do any work that can be classed as strenuous, for it seems to consist of rushing up and down the room, shouting at the top of her voice, and generally making use of her piercing tones - nothing more.

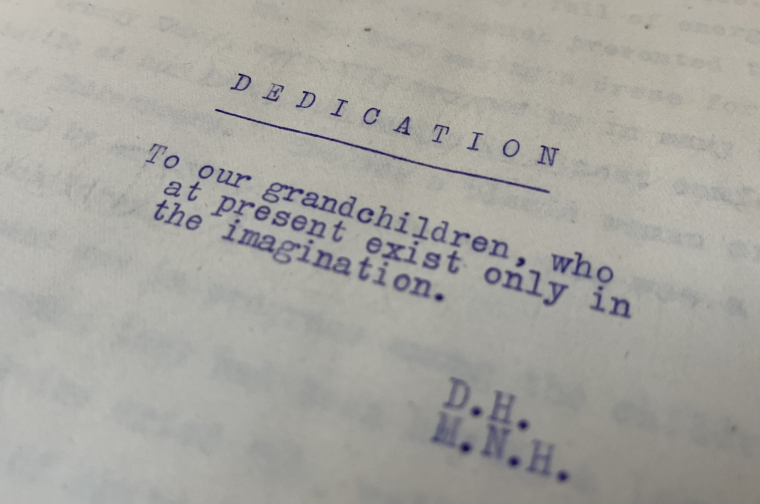

There is a youthful joy to the book, which is incredibly charming. It opens with a time jump to the 1970s, where the sisters are grandmothers, recounting to their numerous, hypothetical grandchildren with what life was like during the Great War. The dedication at the front of the book is, in fact, made out to these possible children.

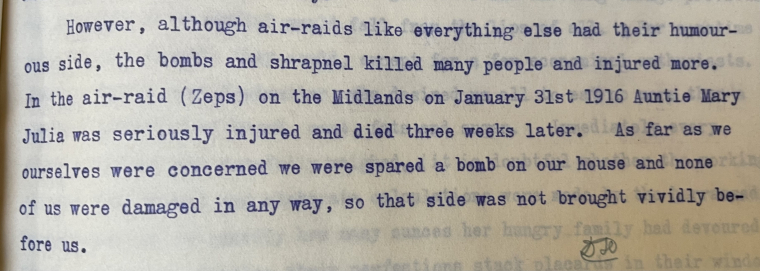

Even when describing events that could be seen as deeply traumatic, such as air raids and zeppelin attacks, there is initially excitement and wonder.

We could hear a good many guns, as well as our own most vigorous one, and see the shells bursting overhead and all round the Zep. Once it gave a lurch and we thought it was hit - great excitement! It was the prettiest sight. The numerous searchlights, which followed its course all the time, made the Zep a lovely golden colour and it seemed so small as to be almost a fairy one.

At times, the playful tone can come across as a little bit callous, and there are moments when the sisters describe the actions of their "domestics" in a way that is hard to swallow for a modern reader, but their humanity often makes up for these moments.

The sisters share their experiences in a variety of different formats. Interspersed within the prose are short, lively plays, containing almost exhaustive stage directions. Though it's not clear whether these plays were acted out, or whether they're used as another method of recounting events, they call to mind a form of entertainment to while away the boredom of an air raid. Because yes, as the raids continue through the war, the sisters make it clear that the initial excitement soon fell away, and became more an endurance test of their patience.

In amongst the drama of air raids and gas main explosions, there are extensive sections that tell of food rations and the creative ways in which people fabricated meals from very little. As they say, “Housekeepers became prematurely aged in the effort to devise fatless and meatless dishes of an equally satisfying nature.”. Though, as in all things, access to rations was not always granted equally.

In spite of rationing, delicacies like treacle, jam, marmalade, cheese and currants were but rarely seen. They were sometimes in the shops but only the favoured few were allowed to buy them. In such a case, it was well if you had been far-sighted enough to admit your grocer to the circle of your intimate friends.

As the war progresses, the tone of the story begins to change and develop. Initially, the sisters' reaction to the war is somewhat blasé, with much focus on the mundane aspects and the inconveniences. Though entertaining to read, it can start to feel like the complaints of the privileged. Once Dorothy starts to write about her experiences doing War Work, though, her passion starts to shine through.

After trying her hand at a number of jobs, and often finding herself bored or unsuited, Dorothy eventually found herself volunteering at the Surgical Requisites Association (SRA) in Mulberry Walk, Chelsea. In this role, which she talks at length about, she trains and eventually becomes a fulltime member of the first ever team to develop and apply plaster casts to the injured. Working under Anne Acheson, the inventor of plaster casts, Dorothy - or 'Jane' as she was known by her colleagues - was one of the first people to be trained in how to apply them. She even had a hand in inventing new techniques. She rose through the ranks of the dedicated team, and was awarded with medals for her work.

A soldier in the bus struck by my medals (1), insisted on shaking hands with me "honour to do so”, talking all the time, much to my alarm, for the whole bus listened with interest while he told me his life history.

It should be noted that even though Dorothy seemingly develops a more compassionate side through her work, she still retains her sharp wit.

The final three chapters of the book describe in vivid detail the celebrations that came following the end of the war. The joy and chaos that took place on Armistice Day. Dorothy being invited to a Royal Garden Party with some of her colleagues - where she was told off for standing on a chair. And finally, the parades and celebrations on Peace Day, 19 July, 1919. Reading these pages, I found myself strangely moved, and as the book draws to a close, I found myself even more curious to discover how life progressed for Dorothy and Nancy Hewins.

Further research shows that neither of the sisters married or had the children or grandchildren they had dreamed up. Dorothy struggled with ill health for most of her life before passing away in 1949, aged 53. Nancy enjoyed a creatively fulfilling life, full of adventure. In the 1920s she put together a women-only theatre troupe called Osiris, which toured the country for some four decades. A wonderful piece about Nancy and Osiris was written in the Independent in 1995, that can be read here. She died in 1978, aged 72.

Though the Hewins sisters aren't household names, and material on their lives is relatively scarce, reading this brief memoir has given me such an incredible insight. Not only into their lives, but also into the way London and its people reacted to seismic events by coming together during wartime. For me, that's more than enough reason for them to be celebrated.